Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

RAFTING

RAFTING. The first rafting on the MISSISSIPPI RIVER was done by LEAD miners who constructed platforms from logs to float their ore to St. Louis, Missouri. When the precious cargo was delivered, the logs themselves were sold before the miners again started north to their claims.

The earliest lumbering was probably on the Wisconsin River, where Pierre Grignon had a sawmill operating in 1822. Log rafts and sawn lumber rafts were dispatched downriver to Galena and Dubuque, and sometimes as far as St. Louis. The first documented raft taken through to St. Louis was in the charge of Henry Merill, who refitted it at the mouth of the Wisconsin River, and delivered it to St. Louis in 1839. (1)

In the earliest days the rafts were handled by large swinging oars on the front and rear with three men on each raft. The trip from the northern lumber region to St. Louis depended upon the speed of the current. The usual time required was from six weeks to three months. By 1889 a steamer with three times as much lumber to move could duplicate the same trip in nine to eleven days. (2)

Lumber camps included men of European, French Canadian, and American ancestry. Large crews employed up to sixty men. Work was plentiful, as long as the timber supply in an area lasted. Supplies were hauled to the camps on sleds or occasionally wagons.

Heavy snow actually aided the tree-harvesting process. Once the snow was packed hard, teams of horses were used to pull the heavy logs out of the forest to a skidway. This was made of small logs used to guide the harvested trees down sharp embankments. Large logs were dragged on sleds. Once at the bottom of the hill, the logs were dragged again to the edge of the nearest stream.

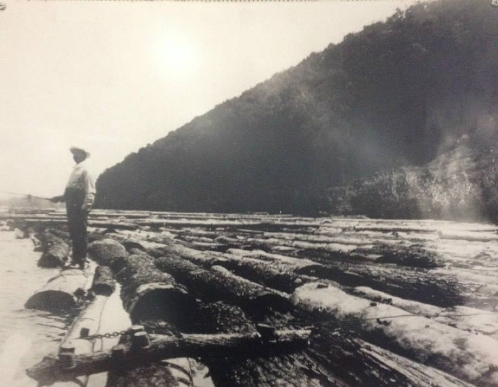

With the coming of spring, the logs, marked by their owners, were floated downstream. Guiding the logs at this stage could often be done from shore with long poles. Where tributaries met larger streams, LOG RAFTS began to be formed. Here the lumbermen had to master the art of running across the logs, freeing those that had become snagged, and guiding the entire collection toward the mill. When logs became jammed the "key log" around which the jam had been created had to be found. Freeing the jam often required tools or dynamite.

While moving the rafts down the Mississippi, lumbermen lived in houseboats or in tents called "wigwams" which were mounted on rafts and floated with the lumber. Samuel Clemens, "Mark Twain" spoke of this:

'I remember the annual processions of mighty rafts that used

to glide by Hannibal when I was a boy, ~ an acre or so of white,

sweet-smelling boards in each raft, a crew of two dozen men or

more, three or four wigwams scattered about the raft's vast level

space for storm quarters, ~ and I remember the rude ways and the

tremendous talk of their big crews, the ex-keelboatmen and their

admiringly patterning successors; for we used to swim out a quarter

or third of a mile and get on these rafts and have a ride.'

Chapter 3, Life on the Mississippi, by Mark Twain. (3)

Log rafts were made up of long "strings" each about sixteen feet wide and about four hundred feet long. The "string" was composed of rows of logs, close together, side by side and end to end. The rows were held together by poles laid across the string and fastened to each log with hickory or elm lockdowns, or plugs. Strings were similarly secured side by side. (4)

Sawed lumber rafts were similarly made up of "strings." The planks were fitted into a frame crate or 'crib' sixteen feet wide, sixteen to thirty two feet long and twelve to twenty inches deep. Sometimes this was built on a tilting platform beside the river, so that the crib when filled could be released into the water. (5) Rafting finished lumber proved impractical as it had to be cleaned and dried out at its destination. (6)

A number of these cribs fastened together would make a raft of perhaps twenty-four cribs for the Chippewa, and from one hundred and twenty to one hundred and sixty cribs for the Mississippi. Rafts were not made up to size until they were safely on the Mississippi. About seven cribs long and one to four strings wide was the usual size run on the tributaries. (7)

Rafts allowed even non-buoyant types of wood to be carried by water. Such types of logs were lashed to logs that would float. This method became essential to the lumber industry after the passage of the Federal Rivers and Harbors Act of March 3, 1899. This act outlawed floating timber on streams in such a manner that would endanger or obstruct steamboats.

Hundreds of logs, rafted downstream at a cost of forty cents per thousand board feet of lumber, were enclosed in a boom fashioned from logs fastened with chains. As the loose logs inside the boom moved downstream they occasionally turned, making the movement by lumbermen over the top of the boom a dangerous venture. Progress downstream was slow. Before the use of steamboats, rafts drifted along at about three miles per hour. In areas where the current was very slow, the raft would have to be "kedged." This process involved a small boat dropping a large anchor ahead of the ponderous raft. The men and sometimes horses on the raft then pulled the raft ahead to the anchor. The process would be repeated many times. (8)

In the early days of floating logs and lumber down the Mississippi, there were five rapids pilots living at Leclaire, Iowa. They were kept reasonably busy piloting floating rafts over the Rock Island rapids. When steamboats started to tow rafts down the Mississippi river, there seemed to be only two of these pilots that were able to make the change successfully--Captain Wesley Rambo and Captain De Forest Dorance. (9)

When boats towing lumber and log rafts reached Dubuque, they did not let other boats pass them before they got to the head of the Rock Island rapids. If a boat got by them, they might be delayed at the head of the rapids waiting for one of these pilots. The rule was always the first boat is the first served with one of these pilots. (10)

Rafting was a difficult business and was not always successful. The following editorial appeared in November 1864: (11)

Lumber Found--On Saturday a lot of about 2,500 feet of

pine boards in the rough and a few planks were picked

up floating in the river. The owner can recover his

property by calling on this office and paying charges.

Late season rafting also proved risky. (12)

Raft Icebound-Mr. Durant from Stillwater arrived last

week with a raft of 600,000 feet of lumber, 100,000 of

which was sold to Joe Rhomberg and the remainder to

Waples & Lumbert to be delivered in the Seventh Street

slough. The high wind of Sunday blew the raft across the

river to the Dunleith shore, where it now lies icebound

with little prospect of getting it back again.

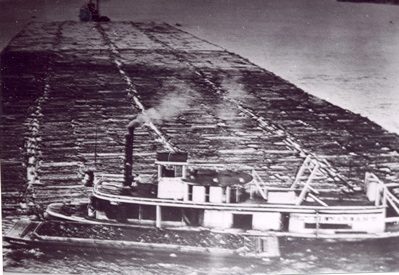

Small steamboats including the "Firefly" and "Alva" were first used to guide the rafts in 1874. The success of the boats heralded a new age in the LUMBER INDUSTRY with the rafts growing larger by the year. Soon scores of boats with such names as the "J. K. Graves," "Neptune," and "Mountain Belle" were competing for the business of pushing the rafts. Each raft contained between one million and three million feet of lumber. The largest rafts were said to be over five blocks long while three blocks in length was considered average. Crews of loggers on such rafts usually numbered eighteen men. Two men were hired as pilots for the boat because the raft was kept moving day and night. There were also two cooks, usually one of the highest paid of the employees, and two firemen in the crew. (13)

With many rafts on the river, confusion sometimes occurred over ownership of logs. In 1880 such a situation led to legal action. (14)

By 1881 there were few days in Dubuque when at least one raft was not stopped at a sawmill or pushed farther south to another mill. The W. J. Young mill in Clinton was the world's largest with the STANDARD LUMBER COMPANY being a close second. The last raft of logs passed beneath the DUNLEITH AND DUBUQUE BRIDGE on August 9, 1915, under the guidance of the "Ottumwa Belle." It was later found to be cheaper to have the timber sawed in the north and shipped south as planks.

---

Source:

1. Steamboat Times. "Log Raft on the Mississippi," Online: http://steamboattimes.com/rafts.html

2. "Rafting on the Mississippi," The Herald, May 26, 1889, p. 4

3. Steamboat Times

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Durban, Richard D. The Wisconsin River: An Odyssey Through Time and Space. Online: http://www.mcmillanlibrary.org/rafting/durbin_rafting.pdf

7. Steamboat Times.

8. 10. Hickman, Nollie. Mississippi Harvest: Lumbering in the Longleaf Pine Belt, 1840-1915. University of Mississippi Press, 2009, Online: http://books.google.com/books?id=4r_oRzkU2RQC&pg=PA110&lpg=PA110&dq=Mississippi+log+rafts&source=bl&ots=l0W1X_m9OA&sig=riR76lNl7CJJuC9YZzrT6bHPT8s&hl=en&sa=X&ei=IhWZU9G6EsSfyAT0z4DQAQ&ved=0CBwQ6AEwADge#v=onepage&q=Mississippi%20log%20rafts&f=false

9. Explorations in Iowa History Project. "The Memories of a Raft Pilot: Captain J. M. Turner." Online: http://www.uni.edu/iowahist/Social_Economic/Raft_Pilot/raft_pilot.htm

10. Ibid.

11. "Lumber Found," Dubuque Democratic Herald, November 13, 1864, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=A36e8EsbUSoC&dat=18641113&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

12. "Raft Icebound," Dubuque Democratic Herald, November 22, 1864, p. 4. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=A36e8EsbUSoC&dat=18641122&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

13. Roseman, Curtis C. and Elizabeth. Grand Excursions on the Upper Mississippi River: Places, Landscapes, and Regional Identity After 1854. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2009. Online: http://books.google.com/books?id=ro6Fsh9m5gsC&pg=PA162&lpg=PA162&dq=Mississippi+log+rafts&source=bl&ots=nKKGH3dM7d&sig=SEugHkOHq8_Fl10qx8BvWazP2bA&hl=en&sa=X&ei=lhKZU_3VBs2TyATOsIKwCg&ved=0CCcQ6AEwATgU#v=onepage&q=Mississippi%20log%20rafts&f=false

14. "Caught on the Fly," Daily Herald, June 19, 1880, p. 4