Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

HOBOS

HOBOS. Hobos were nomadic Americans who began appearing in the 1800s and continued into the 21st century. One frequent hobo in Dubuque was George Hall. Described in 1901 in an article in the Dubuque Telegraph-Herald, Hall was a "veteran hobo and globe trotter." He was easily recognizable by the lack of hair on his head due to sleeping too close to a burning log. On November 17, 1901 he was arrested for "making himself obnoxious" by singing, "When My Can Was Empty" to an audience in the Saengerbund auditorium. (1)

In 1910 an article in the Telegraph-Herald referred to them as "members of the United Order of the Sons of Rest" and "Weary Willies." (2) In 1915 the paper described them as members of the "Amalgamated Order of Non-Workers." (3) Rejecting these labels," hobos took work wherever they could and never spent too long in one place. The Hobo Convention website defines a hobo as this: “hobo wanders and works, a tramp wanders and dreams and a bum neither wanders nor works.” (4)

An article in the Dubuque Telegraph-Herald in 1911 attributed the hobo camp in Dubuque to the decline of MOORE'S MILL. When the supply of logs dwindled, the mill was closed. Around 1900 Martin H. MOORE negotiated with capitalists from Chicago to convert the property into an iron smelter to process ore from the Waukon iron mines. A fire occurred, perhaps caused by one of the hobos who lived in the lumber company ruins, that left nothing but the stone walls.

Under a high cliff that formed the eastern side of the hill lying south of Southern Avenue and within the city limits was a narrow triangular piece of land about one hundred feet wide at the north, its widest end, and running a quarter of a mile south to a spur track of the ILLINOIS CENTRAL RAILROAD up to the old mill. East of this point was RAFFERTY SLOUGH in which many fish could be caught.

It was at the end of a road which was once the spur line roadbed that access to the "hobo jungle could be reached. It was claimed that two hundred feet into the path that it was so dim from weeds and brush that a person could get lost Branches off this path led to different camping grounds. Most of the trails led east toward the slough waters where fish could be caught. Trails leading west became overgrown by fall since these paths only led to "winter quarters" under the cliff.

Camping sites were alike in many respects. A rough fire place was usually constructed in the center with various cooking utensils left in the area. Some camp sites had logs arranged around the fire. Natural caves and abandoned mine shafts made up winter shelter. Fires built near the entrances kept out some of the cold. (5)

Hobos took advantage of the railroad system stretching across state and country, and used them as a way to look for work. As they rested or changed trains, hobos gathered together in areas local residents referred to as "jungles." It was then the job of the police department to run them off. This happened after cases of serious crime, like murder. Soon, however, the hobos returned to their camps.

In May, 1915 eighty-five hobos plus an estimated dozen found in railroad cars were marched out of town by the chief of police, a detective and two officers. Moving along the tracks of the ILLINOIS CENTRAL RAILROAD for nine miles, the hobos were told to keep moving and not come back. After watching the procession for thirty minutes, the police returned to the city. The officers reported that Dubuque seemed to receive a great many hobos with more replacing those arrested or run-out-of-town. Little robbery due to hobos were reported. The newspaper editorialized in the article that "a rock pile would likely solve the problem." (6)

In the mid-1800s, sixty-three hobos formed a tourist union to avoid prosecution for vagrancy. Called Tourist Union #63, they decided that every year a convention would be held for the members to renew friendships, collect dues, sign new members, and honor a king and queen hobo. Kings and Queens were elected to elevate the hobo in the eyes of the public. Each year the gathering hobos honor those they think are the most deserving of their union and those people become king and queen until the next convention. It was at one of these conventions, held in St. Louis in 1889 that the Code of the Rail was drawn up. (7)

An ethical code was created by Tourist Union #63 during its 1889 National Hobo Convention in St. Louis, Missouri. This code was voted upon as a concrete set of laws to govern the Nationwide Hobo Body; it reads this way:

1. Decide your own life, don't let another person run

or rule you.

2. When in town, always respect the local law and officials,

and try to be a gentleman at all times.

3. Don't take advantage of someone who is in a vulnerable

situation, locals or other hobos.

4. Always try to find work, even if temporary, and

always seek out jobs nobody wants. By doing so you

not only help a business along, but ensure employment

should you return to that town again.

5. When no employment is available, make your own work

by using your added talents at crafts.

6. Do not allow yourself to become a stupid drunk and

set a bad example for locals' treatment of other hobos.

7. When jungling in town, respect handouts, do not wear

them out, another hobo will be coming along who will

need them as badly,if not worse than you.

8. Always respect nature, do not leave garbage where

you are jungling.

9. If in a community jungle, always pitch in and help.

10. Try to stay clean, and boil up wherever possible.

11. When traveling, ride your train respectfully, take no

personal chances, cause no problems with the operating

crew or host railroad, act like an extra crew member.

12. Do not cause problems in a train yard, another hobo will

be coming along who will need passage through that yard.

13. Do not allow other hobos to molest children, expose all

molesters to authorities, they are the worst garbage to

infest any society.

14. Help all runaway children, and try to induce them to

return home.

15. Help your fellow hobos whenever and wherever needed, you

may need their help someday.

16. If present at a hobo court and you have testimony, give it.

Whether for or against the accused, your voice counts! (8)

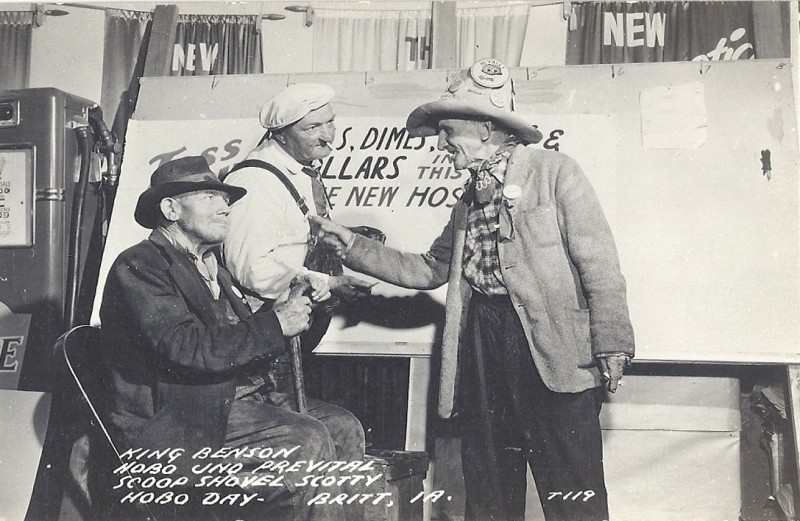

In the 1900s, the citizens of Britt, Iowa convinced the Tourist Union #63 to host its National Hobo Convention in their town. Over 100 years later, the town of Britt is still known as the home for the convention, as well as a huge collection of Hobo artifacts. Every hobo still tries to make it to the annual Hobo convention, which takes place in Britt, Iowa. (9)

---

Source:

1. "Geo. Hall, Old Hobo," Dubuque Telegraph-Herald, November 18, 1901, p. 6

2. "Hobos Begin Annual Move," Telegraph-Herald, March 10, 1910, p. 10

3. "Police Break Up Hobo Convention," Telegraph-Herald, May 23, 1915, p. 14

4. "Hobo Culture," Online: https://uni.edu/carrchl/wp/allaboard/hobo-culture/

5. "Dubuque 'Jungles' Haven of the Hobo," Dubuque Telegraph-Herald, July 30, 1911, p. 4

6. "Police Break Up..."

7. Ibid.

8. "Hobo," Wikipedia, Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hobo

9. "Police Break Up..."