Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

COAL CRISIS

COAL CRISIS. In terms of the production of energy from domestic sources, from 1885 through 1951, coal was the leading source of energy in the United States. Most urban homes had a coal bin and a coal fired furnace.

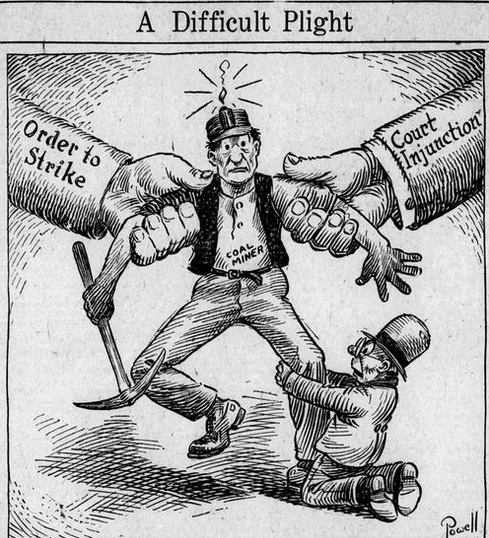

The United Mine Workers under John L. Lewis announced a strike for November 1, 1919. They had agreed to a wage agreement to run until the end of WORLD WAR I and now wanted capture some of their industry's wartime gains. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer invoked the Lever Act, a wartime measure that made it a crime to interfere with the production or transportation of necessities. The law, meant to punish hoarding and profiteering, had never been used against a union. Certain of united political backing and almost universal public support, Palmer obtained an injunction on October 31 and 400,000 coal workers struck the next day. (1)

In December, 1919 the federal government sought no compromise with mine workers whose walkout resulted in a nationwide emergency. The federal fuel administrator announced that after December 2nd only essential consumers in the first five classes of the war priorities list would be supplied with coal. Railroad administration officials announced that the order meant the closing of industrial operations. Public utilities were order to produce only sufficient light, power, and heat to meet urgent needs. (2)

In Dubuque street car service was cut in half with the exception of rush hour. Electric power to all factories was stopped at 4:00 p.m. every afternoon. All electric signs were discontinued as were street lights with the exception of Saturday night when they were lit until 9:00 p.m.. Offices were closed except between 9:00 a.m. and 4:00 a.m. and night shifts were eliminated. Some cities had to cut of electric lower to all consumers for at least three days per week. (3)

As the strike dragged on into its third week, coal supplies were running low and public sentiment was calling for ever stronger government action. The final agreement came on December 10. The deal amounted to a 14% wage increase as well as an appointment of an investigatory commission to continue the exploration of the wage issue. The agreement was signed by John L. Lewis, John Brophy and other officials, and called on the miners to return to work. (4)

In 1950, about 19% percent of the coal consumed was for electricity generation. (5) Early in the year, workers in the bituminous coal fields of Illinois went on strike. This spread nationwide. Unemployment across the nation soared to an estimated 200,000 as workers in coal-related industries joined 372,000 striking mine workers. (6)

On February 28, 1950 the Dubuque City Council met to discuss the city's critical coal shortage. Ways of distributing any available coal had been discussed the previous day by members of the board of education and other institutions with coal dealers. Concerns about rationing were expressed with ways in which hoarding could be avoided. It was known that some people were calling all the coal dealers and buying all they could from each one. It was decided that a clearinghouse plan should be adopted in which all orders had to proceed through one site. Making matters worse was a spreading case of INFLUENZA in the city. Dealers believed those homes with illness should get priority, but questioned how illness could be proved. (7)

The plan established was for all orders for coal received by dealers to be forwarded to the police department. The police would check the lists for duplication and spot-check homes to see if the coal was really needed. The school district stopped all extra-curricular activities and night school and announced that it had between two and three weeks of coal left for heating. ST. JOSEPH'S SANITARIUM was operating on a day-to-day basis, FINLEY HOSPITAL (THE) had a four to five day supply, and MOUNT PLEASANT HOME had enough coal to last one week. (8)

The end of the strike came by March 6, 1950. The school district's curtailment of activities ended on March 9, 1950. (9) Supplies came slowly. By May 3, 1950 MAIZEWOOD INSULATION COMPANY was able to reopen after closing for a week due to the lack of coal. (10)

Source:

1. "United Mine Workers Coal Strike of 1919," Wikipedia, Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Mine_Workers_coal_strike_of_1919

2. "Text of Order Which Curtails City Industries," Telegraph-Herald, December 2, 1919, p 1

3. "Electric Power to Stop at 4 P.M.; Car Service Cut," Telegraph-Herald, December 2, 1919, p. 1

4. "United Mine Workers..."

5. "Energy Policy of the United States," Wikipedia. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_policy_of_the_United_States

6. "Number of Idle in U.S. Soars Upward," Telegraph Herald, March 1, 1950, p. 1. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=aEyKTaVlRPYC&dat=19500301&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

7. "City Council Called in Crisis to Plan Coal Distribution," Telegraph Herald, February 28, 1950, p. 1. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=aEyKTaVlRPYC&dat=19500228&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

8. Ibid., p. 6

9. "Schools Sight Coal, Life Ban," Telegraph Herald, March 9, 1950, p. 17. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=aEyKTaVlRPYC&dat=19500309&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

9. "Strub Tells Cops' Role in Coal Crisis," Telegraph Herald, May 3, 1950, p. 2. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=aEyKTaVlRPYC&dat=19500303&printsec=frontpage&hl=en