Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

MCINNERNEY, Thomas Henry

MCINNERNEY, Thomas Henry. (Dubuque, IA, May 8, 1867--Greenwich, CN, Sept. 30, 1952). McInnerney's father was an associate of Joseph "Diamond Jo" REYNOLDS. McInnerney began work as a cash boy for the H. B. GLOVER COMPANY at twenty-five cents a day with hours from 7:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Monday through Friday with an additional four hours on Saturday. (1)

McInnerney studied pharmacy at the University of Illinois in 1893 and borrowed $10,000 to open a drug store at Chicago's 35th Street and Indiana Avenue. He sold the store for $20,000, moved to Manhattan ,and became the drug department manager of the Siegel, Cooper and Company department store. (2) Informed that the department was not making money, McInnerney said the owner was lying and quit. The following day, the owner called him back in and offered him participation in the department's profits. The first year, he made $4,000 and the second year he earned $16,000. (3)

McInnerney moved to Chicago in 1911 with a partial ownership in a coal company which operated an ice cream division. He traded his interest in coal for the control of the ice cream portion of the business. By 1920 he was doing a million-dollar-a-year ice cream business in Chicago. It was during this time that he began thinking about consolidating the dairy products industry.

In 1923 McInnerney sold the milk-consolidation idea to the investment firm of Goldman-Sachs, Lehman Brothers, and Tobey and Kirk. (4) The firms underwrote the business for $55 million. The resulting National Dairy Products Corporation was organized in New York City and incorporated in Delaware in December 1923.

The company was formed for the purpose of acquiring the common stock of the Rieck-McJunkin Dairy Company of Pittsburgh and the Hydrox Corporation of Chicago, two of the largest manufacturers and distributors of ice cream and dairy products in the United States. Management of the new company was made up of the presidents of both acquired firms: Edward E. Rieck, President of Rieck-McJunkin, who became chairman of National Dairy, and Thomas McInnerney, president of Hydrox, who became president of the new firm. (5)

The business plan included purchasing or constructing a series of plants through the acquisition of existing businesses strategically located throughout the country. Each subsidiary was to retain its own name and personnel. This strategy was expected to require lower inventories, more rapid turnover, and shorter credits. (6)

Within months, National Dairy began acquiring other companies. In 1925 alone it puyrchased eighteen similar businesses. By 1926 it owned such well-known dairy firms as Breyer Ice Cream of Philadelphia, Harding Ice Cream of Nashville, and Sheffield Farms of New York. In 1926 National Dairy operated in 1,600 cities and towns in thirteen states from New York to Nebraska. Profits in 1925 were $4.9 million from sales of $105.3 million. (7)

National Dairy employed approximately 35,000 people by 1930 and earned $26.3 million from sales of $374.6 million. On the basis of both sales volume and profits it claimed the honor of being the largest food products company in the country by a wide margin. Soon, National Dairy began acquiring companies outside of dairy products, purchasing Deerfoot Farms of Boston, a manufacturer of sausages. It also formed National Juice Corporation to produce orange juice in Tampa, Florida, which was then distributed through regular milk routes. (8)

National Dairy made its largest acquisition by adding Kraft-Phoenix Cheese Corporation in 1930. At the time, the company was responsible for selling forty percent of all the cheese purchased in the United States. (9) Since Kraft alone earned over $86 million, this brought National Dairy's sales up to over $400 million.

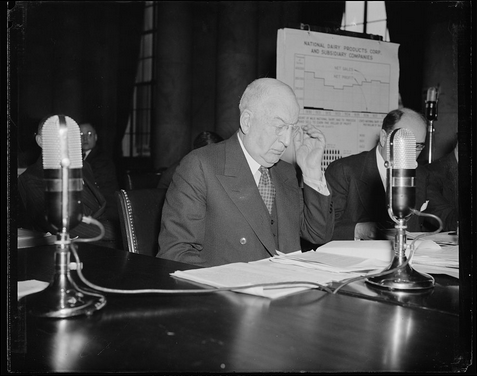

The growth of certain companies by acquisition of other companies in the same industry did not escape the notice of the United States Congress. The National Monopoly Investigating Committee called McInnerney to testify. He assured the committee that there never had been and did not exist any possibility of monopoly in milk distribution. (10)

Sales and earnings growth moderated for National Dairy during the 1930s. The retail milk distribution industry was particularly competitive and highly regulated so the company attempted to diversify its line of manufactured milk products. (11)

National Dairy earned $11.1 million on sales of $347.4 million in 1940. Demand for milk, cheese, and other dairy products soared during the wartime years for both civil and military customers. In 1941 the company reported record earnings of $83.6 million on sales of $431 million; in 1944 new records were set again when the company achieved sales of $593.9 million. Sales to the United States military represented a major portion of these sales. Deliveries to the United States government in 1944 included 48 million quarts of milk, 8.5 million gallons of ice cream, 101 million pounds of cheese, 23.5 million pounds of butter, 500,000 pounds of other Army and Navy ration spreads, ten million pounds of margarine, 4.5 million pounds of powdered milk, one million cases of evaporated milk, 769,000 gallons of salad dressing and three million cans of Tushonka, a Russian Army meat ration. (12)

In the years of 1945 through 1960, National Dairy spent more than $100 million expanding and modernizing plant and equipment as well as building a new research laboratory. In 1948 sales reached $986.4 million, the highest in the company's twenty-five-year history. (13)

During the 1950s, National Dairy invested heavily in new equipment, spending $230 million between 1945 and the end of 1953. In 1956 the company acquired Metro Glass Company, a maker of glass containers used by National Dairy. The company also constructed new plants in Germany, Australia, and England, indicating the growing importance of non-U.S. sales to National Dairy. In 1961 it entered the fish business by purchasing Green's Products, Ltd., the largest canner and distributor of tuna fish and salmon in Australia. (15)

In 1962 increasing consumption of dairy products by the U.S. public, aided by the introduction of new products and advertising, helped National Dairy achieve record sales $1.82 billion. These new products included a liquid high-protein weight control product called “Sealtest 900 Calorie Diet.” (16)

In 1969, the firm changed its name from National Dairy to Kraftco Corporation. The reason for the name change was given at the time: "Expansion and innovation have taken us far afield from the regional milk and ice cream business we started with in 1923. Dollar sales of these original products have remained relatively static over the past ten years and, in 1969 accounted for approximately 25% of our sales." At the same time, the firm relocated to Glenview, Illinois, in 1972. (17)

In 1976, its name changed to Kraft, Inc. to emphasize the trademark the company had been known for and as a result of the fact that dairy, other than cheese, was now only a minor part of the company's sales. Reorganization also occurred after the name change. (18)

---

Source:

1. "Tycoon Tells of Early Days," Telegraph Herald, February 12, 1950, p. 17. Online: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=aEyKTaVlRPYC&dat=19500212&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. National Dairy Products Corporation. Lehman Brothers Collection. Online: http://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/lehman/chrono.html?company=national_dairy_products_corporation

5. "Tycoon..."

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. "Thomas H. McInnerney: National Dairy Corporation," Online: https://www.hbs.edu/leadership/20th-century-leaders/Pages/details.aspx?profile=thomas_h_mcinnerney

10. PICRYL. Online: https://picryl.com/media/no-possibility-of-monopoly-in-milk-distribution-witness-tells-monopoly-investigating

11. "Tycoon..."

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.