Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

LABOR MOVEMENT

LABOR MOVEMENT. The rise of the organized labor movement in Dubuque began with the rise of industrialization in the 1850s. Dubuque's first union belonged to the typographers during that decade. By the mid-1880s, however, the typical worker labored ten hours per day, six days a week for wages that were based on age, gender and race.

Dubuque was the largest manufacturing city in Iowa during the 1880s. A profile of the city's working-class population in the mid-1880s indicates that a typical worker was employed ten hours daily with wage rates determined by age, job, and sex. Women and children, involved in low-paying factory, retail and service occupations, earned the least. Wages earned by women average one-third to one-half those of men. Boys received less than women and girls made less than boys. Common male occupations included blacksmiths, carpenters, machinists, railway workers, and teamsters. Unskilled male workers earned from $1.00 to $1.50 daily as compared to bricklayers who earned from $3.75 to $4.00. Common laborers rented homes while between one-third and one-half of the tradesmen owned their own homes. (1)

Prior to 1885, trade unions in Dubuque existed among printers, cigarmakers, locomotive firemen and engineers, tailors and bricklayers. Membership varied from twenty to forty. These groups protected their independence, decided work rules and wage scales, avoided politics, and held regular meetings. (2)

The lowest paying jobs belonged to women and children who worked in service and retail jobs. Men earned one-third more than women. Women received more than boys who earned more than girls. AFRICAN AMERICANS were left with work as cooks, servants or porters. Close supervision in the workplace meant little rest time, but many opportunities to be injured or die. Bad ventilation, explosions, fires, and unsafe machinery were common. Faced with such working conditions, workers attempted to band together.

Attempts to organize and bargain for wages and working conditions required courage. Opposition to organized labor came from company management that resisted even recognizing union spokespersons. Union organizers were dismissed. Lockouts and strikebreakers were employed; labor organizers often found public officials tending to side with management.

One of the first major breakthroughs in labor organizing in Dubuque came in the 1880s when the KNIGHTS OF LABOR organized building tradesmen and women garment workers at the H. B. GLOVER COMPANY and railroad workers on the Chicago and Northwestern.

In 1887 efforts of Dubuque manufacturers to lobby the Iowa Legislature to block passage of Iowa's first factory inspection acts led the Knights to organize a political party. The Labor Reform Party successfully elected Dubuque's first "labor" MAYOR, captured control of the city council and carried all other citywide offices. The January 1, 1887 of the Industrial Leader encouraged readers to follow independent political action. In February, a full slate of labor candidates was assembled for the municipal election. The Labor Reform Party declared the intention:

to have laws made and executed in the interest

of justice, of morality, and of productive labor;

so that the workers, who produce all the wealth,

may not sink into deeper poverty, while the idle

drones, who produce none, revel in increased

opulence. (23)

Party planks addressed extravagance in the budget, inequitable taxes, rising debt, the contract labor system of performing street work, and monopolistic practices of 'corrupt rings and political tricksters.' (24)

The results of the election were surprising. The Republican and Democratic strategy of portraying themselves and better for the general public failed. The entire Knights of Labor ticket were elected. Christian Anton VOELKER was elected mayor and John STAFFORD became the city recorder. (25)

The new council took controversial positions. In May the entire police force was discharged amid charges that it had been used to harass workers. Half of the new force was former officers and the other half all Knights. The subcontracting of labor was street work was abolished and replaced with day labor and the council gave a 40% increase in the daily wage for city work from $1.25 to $1.75 which was higher than wages paid to private sector labor. (26) The council also rejected the offer of the county supervisors to have county jail prisoners to city work. The council responded by claiming the use of such labor depressed wages, offered unfair competition, and was nothing other than involuntary servitude. (27)

When the Knights swept into office, Dubuque's total indebtedness exceeded $800,000--the highest of any city in Iowa. Working on their pledge to begin a more equitable system of taxation, the council instituted a 20% increase in city tax assessments. As a result, the indebtedness dropped about 15% allowing community projects that had been stopped to pay for debt service. (28)

During the time the Knights held public office, the goods and services produced in the city increased 20%; the local transportation system improved with two new railway lines, a new ferry company, a high bridge across the MISSISSIPPI RIVER; and a new fire alarm system was installed. (29)

Despite the achievements, political power for the Knights was soon ended. The local press and the Board of Trade attacked the new political party which was split by potential offers to join with one of the two major political parties. Within the Knights, arguments developed between those who believed in getting elected and those who felt lobbying was more effective. (30)

The fall election of 1887 brought Democrats back into power while the labor vote declined by 45%. In 1888 the Knights did not offer a separate ticket of candidates. The Citizen's Party of half Republicans and half Democrats won nearly all the city offices and most of the council seats. The Knights were never again to play an important role in local politics and they left independent politics in 1890. (31)

The unexpected death of John Stafford, weakened patronage of the cooperatives, and election defeats all conspired to further weaken the Knights locally. In one of its last efforts, the Knights led the efforts in forming the DUBUQUE TRADES AND LABOR CONGRESS, a citywide labor organization in July 1888. (32)

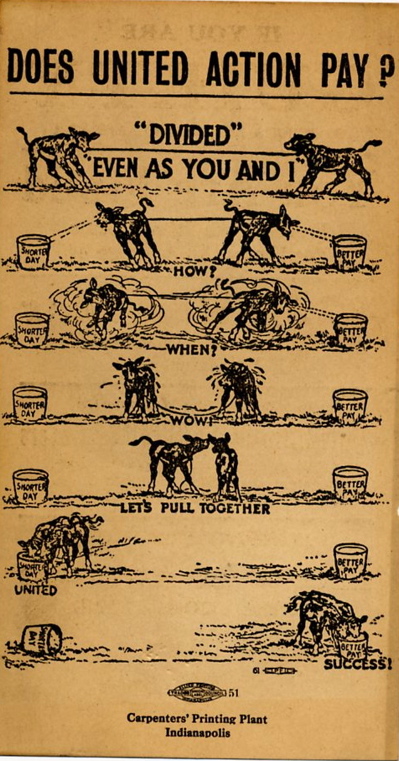

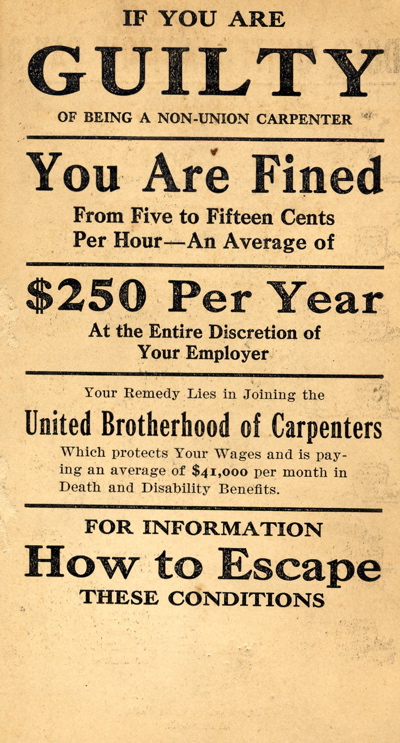

Union organizing efforts from 1890 to 1910 focused on the building trades. Painters, iron workers, bricklayers, carpenters, sheet metal workers, and plumbers organized independent locals for each trade. Together these locals formed the Building Trades Council. The Teamsters became one of Iowa's strongest unions through help they received from the building trades.

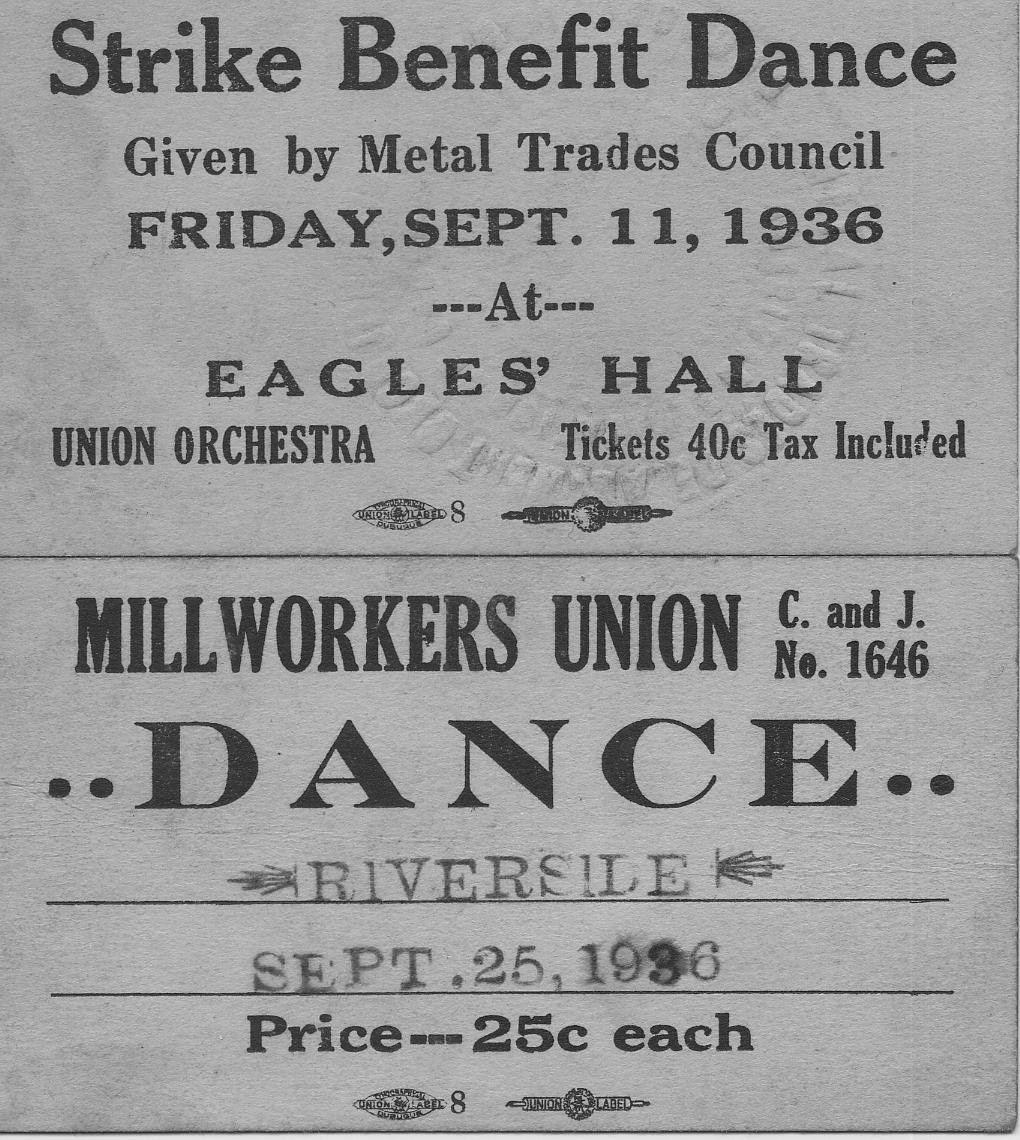

By 1910 the estimated fifty unions operating in Dubuque made the city Iowa's labor movement stronghold. The local unions gained additional strength when they joined to form the Dubuque Trades and Labor Congress. The largest unions were those of the coopers, retail clerks, cigar makers, brewery workers, machinists, iron molders, and street railway employees. Despite several organizing campaigns, mill workers at the sash, door and blind factories of FARLEY AND LOETSCHER MANUFACTURING COMPANY and Carr, Ryder, and Adams remained unorganized until the mid-1930s.

Through WORLD WAR I, the role of organized labor in the business climate of Dubuque was controversial. Powerful unions were charged with obtaining wages too high for Dubuque manufacturers to compete economically with other major Iowa employers or to attract new industry. The HARMONY MOVEMENT, according to labor leaders, sought to weaken efforts to unionize companies. Labor advocates charged that some local businessmen conspired to keep new industries out of Dubuque to maintain a large pool of potential labor.

Hard times for organized labor came during the 1920s. The" open shop" concept in which there was no recognition of organized labor was, it was claimed, renamed the "American Plan" to hide its anti-union nature. The machinists at KLAUER MANUFACTURING COMPANY and A.Y.MCDONALD MANUFACTURING COMPANY lost strikes.

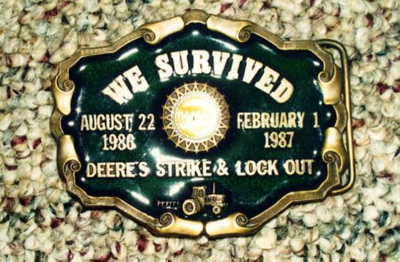

The Great Depression of the 1930s led to a revived labor movement. In 1933 the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen organized at the DUBUQUE PACKING COMPANY. Bell Telephone workers were organized later in the decade by the Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO). A bitter strike against ROSHEK'S DEPARTMENT STORE led to renewed strength in the Teamster's Union. The Upholsters campaigned to organize FLEXSTEEL INDUSTRIES, INC. and the farm equipment workers. In 1948 the United Auto Workers were successful at the JOHN DEERE DUBUQUE WORKS.

Recent years have witnessed fewer strikes and increased labor-management cooperation as the threat to American jobs is seen from foreign competition. Cooperation between labor and management led to the development of the DUBUQUE AREA LABOR-MANAGEMENT COUNCIL. Leadership of organized labor through these changing times has been provided by such leaders as Hugh D. CLARK,John GROGAN and Mel MAAS.

On July 1, 1975 collective bargaining was approved in Iowa for public school employees. Teachers in the DUBUQUE COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT voted to have the DUBUQUE EDUCATION ASSOCIATION, a representative of the National Education Association, represent them and the first negotiated agreement with the District was written.

---

Source: