Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

UNDERGROUND RAILROAD: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

A similar story about Dubuque's connection to the Underground Railroad was recounted by Matt Parrott, newspaper editor and Lieutenant Governor of Iowa, in ''The Midland Monthly'' in 1895. In this short article, Parrott described efforts to transport a runaway slave by wagon from an undisclosed location in Eastern Iowa to Dubuque where the runaway would be turned over to someone "who would then help him on his way to Canada." (3) | A similar story about Dubuque's connection to the Underground Railroad was recounted by Matt Parrott, newspaper editor and Lieutenant Governor of Iowa, in ''The Midland Monthly'' in 1895. In this short article, Parrott described efforts to transport a runaway slave by wagon from an undisclosed location in Eastern Iowa to Dubuque where the runaway would be turned over to someone "who would then help him on his way to Canada." (3) | ||

An intriguing possible role of the Dubuque-St. Paul Trail established in 1854 has been suggested. Among the members of William Stork anti-slavery group in Harmony, Minnesota were After Hoag and Daniel Dayton, owners of the Ravine House in Big Springs, a stagecoach stop along the Dubuque-St. Paul Trail. Historical research has established that fugitive slaves used stagecoach routes to escape. Some were hidden in secret compartments of wagons. Stops like Ravine House built in 1855 were used to shelter them as they traveled. (4) | |||

For further reference, see the entry [[AFRICAN AMERICANS]]. | For further reference, see the entry [[AFRICAN AMERICANS]]. | ||

| Line 38: | Line 40: | ||

2. Hogstrom, Erik, "In Search of Freedom," ''Telegraph Herald'', January 26, 2025, p. 1 | 2. Hogstrom, Erik, "In Search of Freedom," ''Telegraph Herald'', January 26, 2025, p. 1 | ||

3. Parrott, Matt, "An Underground Railroad Incident," ''The Midland Monthly'', May 1895, Volume 3, Number 5, pages 479-480. Online: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Midland_Monthly/tZlBAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA479 | 3. Parrott, Matt, "An Underground Railroad Incident," ''The Midland Monthly'', May 1895, Volume 3, Number 5, pages 479-480. Online: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Midland_Monthly/tZlBAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA479 Special credit to: Steve Hanken | ||

4. Hahn, Amy Jo, "Discovered — The Underground Railroad in Southeast Minnesota and the Abolitionists Who Helped." April 15, 2025, Online: https://rootrivercurrent.org/tthe-underground-railroad-in-southeast-minnesota-and-the-abolitionists-who-helped/ | |||

Latest revision as of 22:38, 22 January 2026

UNDERGROUND RAILROAD. The National Park Service has summarized the existence of the Underground Railroad as the following:

The Underground Railroad—the resistance to enslavement through escape and flight,

through the end of the Civil War refers to the efforts of enslaved African Americans

to gain their freedom by escaping bondage. Wherever slavery existed, there were

efforts to escape. At first to maroon communities in remote or rugged terrain on

the edge of settled areas and eventually across state and international borders.

These acts of self-emancipation labeled slaves as "fugitives," "escapees," or

"runaways," but in retrospect "freedom seeker" is a more accurate description.

Many freedom seekers began their journey unaided and many completed their self-

emancipation without assistance, but each subsequent decade in which slavery was

legal in the United States, there was an increase in active efforts to assist

escape.

The decision to assist a freedom seeker may have been spontaneous. However, in some

places, especially after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the Underground Railroad

was deliberate and organized. Despite the illegality of their actions, people of all

races, class and genders participated in this widespread form of civil disobedience.

Freedom seekers went in many directions – Canada, Mexico, Spanish Florida, Indian

Territory, the West, Caribbean islands and Europe. (1)

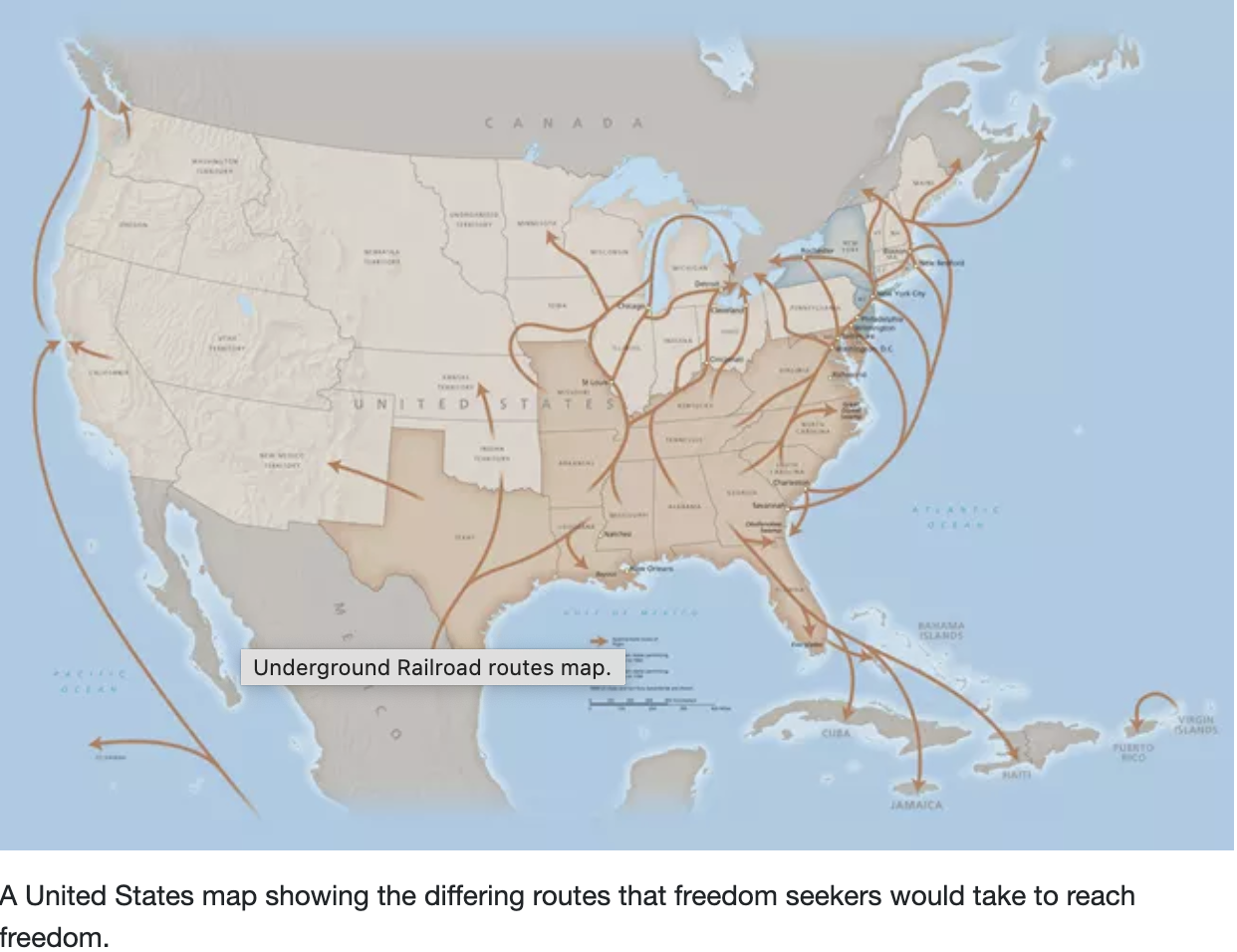

This map shows that participation of people as "conductors" and the establishment of "stations" at which escaping slaves were hidden until they could be moved further north was a southern Iowa activity. The community of Salem, Iowa in the 1840s was the home of Henderson Lewelling who promoted abolition so strongly that he was ousted from meetings of other Quakers. His home was constructed to hide slaves with a trapdoor cut in the kitchen floor leading to a hollowed out area in which slaves could be hidden. Tour guides of the home in the 1980s suggested the theory that the trapdoor and crawl space may have even been part of a tunnel connecting Henderson's house with the home of his brother across the street. Lewelling left Salem for the Pacific Northwest long before the Civil War.

Questions remain of the involvement of Captain Charles Merry in East Dubuque, Illinois. Merry constructed a large home near the bayous of the Mississippi River. Boats with cargo could be paddled up to the house and their cargo unloaded unseen. A small entrance located at the side of house and near water level led to the basement. It has been said that shackles were found pinned to the walls years after the Merry family left the area. Some references to Merry contain a reference to "underground railroad" with a (?). The home also had tunnels leading from the rear of the house up the hill. Was Lewelling posing as a "conductor" only to capture escaped slaves and then resell them to slave hunters? Proof either way has not been found.

Dubuque likely had a role to play in the Underground Railroad. There were residents of the community who advocated for abolition, and in an issue of the Telegraph Herald, a portion of a 1911 family history of Samuel B. Hampton relates that Hampton hid runaway slaves among furniture loaded in a wagon. From Viola, Iowa he traveled through Dubuque going north to Canada. (2)

A similar story about Dubuque's connection to the Underground Railroad was recounted by Matt Parrott, newspaper editor and Lieutenant Governor of Iowa, in The Midland Monthly in 1895. In this short article, Parrott described efforts to transport a runaway slave by wagon from an undisclosed location in Eastern Iowa to Dubuque where the runaway would be turned over to someone "who would then help him on his way to Canada." (3)

An intriguing possible role of the Dubuque-St. Paul Trail established in 1854 has been suggested. Among the members of William Stork anti-slavery group in Harmony, Minnesota were After Hoag and Daniel Dayton, owners of the Ravine House in Big Springs, a stagecoach stop along the Dubuque-St. Paul Trail. Historical research has established that fugitive slaves used stagecoach routes to escape. Some were hidden in secret compartments of wagons. Stops like Ravine House built in 1855 were used to shelter them as they traveled. (4)

For further reference, see the entry AFRICAN AMERICANS.

---

Sources:

1. "Underground Railroad," National Park Service, Online: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/undergroundrailroad/what-is-the-underground-railroad.htm

2. Hogstrom, Erik, "In Search of Freedom," Telegraph Herald, January 26, 2025, p. 1

3. Parrott, Matt, "An Underground Railroad Incident," The Midland Monthly, May 1895, Volume 3, Number 5, pages 479-480. Online: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Midland_Monthly/tZlBAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA479 Special credit to: Steve Hanken

4. Hahn, Amy Jo, "Discovered — The Underground Railroad in Southeast Minnesota and the Abolitionists Who Helped." April 15, 2025, Online: https://rootrivercurrent.org/tthe-underground-railroad-in-southeast-minnesota-and-the-abolitionists-who-helped/