Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

BUTTON INDUSTRY: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (25 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image:button.jpg| | [[Image:button.jpg|left|thumb|250px|Button making from clam shells was once one of the largest industries in eastern Iowa.]] | ||

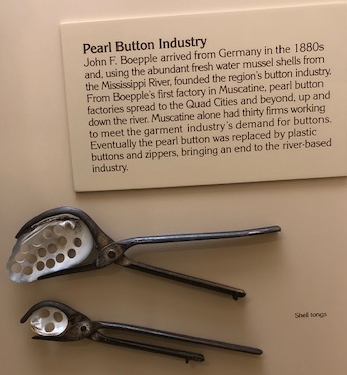

[[Image:shells.jpg|left|thumb|250px|Shells like these from which button blanks were removed may still be found along the Mississippi River.]]BUTTON INDUSTRY. | [[Image:clam tongs.png|left|thumb|250px|Clam tongs. Photo courtesy: Putnam Museum, Davenport, Iowa]] | ||

[[Image:shells.jpg|left|thumb|250px|Shells like these from which button blanks were removed may still be found along the Mississippi River.]]BUTTON INDUSTRY. Mussels gathered from the rivers of the Mississippi watershed have supported two important industries and provided millions of dollars of income to land-based and river-based men and women starting in the 186Os. | |||

Collecting freshwater pearls was the reason at first forharvesting shellfish from 1860 to 1900. The revenue for a single pearl was often in the thousands of dollars. "Pearl rushes" along a river created boomtown like environments which attracted local, as | |||

well as out-of-state, mussel-hunters and buyers. Proceeds from pearls brought to many individuals instant fortune and had an unheralded role in the capitalization of rural America prior to 1930. Pearl revenue exceeded all other natural product industries combined, excepting timber, in many areas. | |||

Most important of the commercial uses of river shellfish was the production of buttons from 1891 until approximately 1950. Shell buttons were made of both pearly ocean and freshwater shell for centuries in Europe before being manufactured in the northeastern United States beginning in the 1850s. The United States product, based on imported material, had a hard time competing with the European product, and the industry was dying out in 1890. (1) | |||

The industry was brought to the midwestern United States by [[BOEPPLE, John|John BOEPPLE]], a former German button maker, who was accustomed to using animal horn, hooves, bone and seashells. (2) In 1887 while looking for shells that were cheaper than those from the ocean for button production, he found several suitable beds of clams in rivers leading to the Mississippi. (3) In 1891 he established the Boepple Button Company, a pearl-button factory in Muscatine, Iowa. (4) In June 1900 near the mouth of [[CATFISH CREEK]] a small colony of clammers developed called "Pearl City." Living in tents, the clammers worked from June through October. (5) | |||

The slow pace of recruitment led the local press to remind workers that the job offered year-round employment. By 1902 the plant needed to be expanded. Cellars beneath the factory were said to store $45,000 worth of shells for winter processing. | [[Image:hookedclams.jpg|left|thumb|250px|Photo courtesy: National Mississippi River Museum and Aquarium]]Clamming was a low cost operation. Using a boat, a clammer would drag a rod with perhaps one hundred hooks along the river bottom. The clams would snap shut on the hook and be caught. The rod would be raised, the clams removed and the process repeated. Once the boat was full, it would be rowed to shore and unloaded. A clammer could earn three dollars for a full boat with the chance of finding a pearl which could bring one hundred dollars or more. (6) | ||

The clams were placed in water and boiled. The meat was removed, checked for pearls, and then discarded or sold to farmers for hog feed or to fishermen for bait. It was also used for dog and cat food. (7) The shells were immediately sold to buyers or shipped to button factories. (8) | |||

The industry caused an economic ripple effect into related industries such as housing and merchandising. Population increased in river cities as workers moved to new jobs that provided attractive year-round working conditions. The industry led to the development of a new group of wealthy Iowans who built mansions and invested their profits throughout their communities. The industry was not confined to cities along the Mississippi. In 1898 a large pearl button factory was opened in Vinton, Iowa by the Waterbury Button and Electric Company and local investors. Capitalized at $20,000, the company provided employment for between 70 and 100 people. Shells came from the Cedar River. (9) | |||

Dubuque had the advantage of being close to the clam beds. In May, 1898 the ''Dubuque Herald'' reported "car loads of our mussel shells are being taken away." The article noted that the shells were destined for Muscatine, Iowa and a large pearl button factory. The article continued-- | |||

This new industry certainly opens a line of | |||

employment which operates in an entirely new | |||

field, and takes away many bushels of shells | |||

which had always been considered worthless.. | |||

it is said in new territory men can make very | |||

good wages at gathering them. (10) | |||

The city also had a large source of labor and connections to cities of the eastern United States by [[RAILROADS]]. In March 1889, the Standard Pearl Button Company moved its machinery to Dubuque from Charles City. John Boepple visited Dubuque in 1898 and suggested his interest in moving his entire operation north from Muscatine if his moving expenses were reimbursed. This, however, was never done. | |||

[[Image:plug.jpg|left|thumb|250px|This cylinder cut from a clam shell needs to be finished. These are rare finds today.]]The largest button-making company to move to Dubuque was that of Harvey Chalmers and Son that established its own blank-cutting plant in the city in 1901. The company owned and operated the largest pearl button factory in the United States at Amsterdam, New York. At this plant, which employed an estimated 300 workers, only the finishing process in the manufacture of buttons was carried out. The rough work was carried out at branch locations like Dubuque. (11) Dubuque officials promised the company, named the Iroquois Pearl Button Company, the plant site for five years and installed the company's power plant for a total cost estimated to be $2,500. (12) The company promised to employ at least 150 men 300 days annually for a period of at least five years. If the company made good on its promises, it would receive a $500 bonus at the end of each year until the term of the agreement (five years) expired. The company posted a guarantee of $2,500 to ensure its good faith. (13) The company's location near the levee included three large buildings and two hundred button machines. (14) | |||

[[Image:womenbutton.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Women working in a button-making factory. Photo courtesy: National Mississippi River Museum and Aquarium]] | |||

With equipment sufficient to need a workforce of four hundred, the Iroquois Company encouraged employment by offering the unique opportunity for workers to earn money from the first day of employment, although at a reduced rate, while they were being trained. Similar factories paid no wages for the first two weeks. Women's jobs in button manufacturing were usually limited to the less skilled and lower paying positions. Cutters made an average of $8 to $10 a week. "Facers," drillers and packers—all positions filled by women—were paid between $4 and $6 a week. (15) | |||

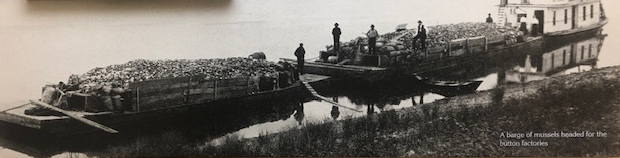

[[Image:clambarges.png|right|thumb|250px|Barges loaded with clam shells headed for the factory. Photo courtesy: Putnam Museum, Davenport, Iowa]]The slow pace of recruitment led the local press to remind workers that the job offered year-round employment. By 1902 the plant needed to be expanded at a cost of $30,000. (16) Cellars beneath the factory were said to store $45,000 worth of shells for winter processing. | |||

Due to the size of its operation, the Iroquois plant was able to weather the financial collapse of the industry caused by speculation in 1903-1904. | Due to the size of its operation, the Iroquois plant was able to weather the financial collapse of the industry caused by speculation in 1903-1904. | ||

Many factors led to the demise of the pearl button industry. Plastics developed near the time of | [[Image:buttoncard.jpg|left|thumb|250px|]]Many factors led to the demise of the pearl button industry. Plastics developed near the time of World War II offered more variety in size, shape, and color than pearl buttons at much less cost. The ability of plastics to withstand detergents in washing has also been suggested. Construction of dams on the Mississippi and poor agricultural practices leading to erosion led to increased silting of the river bottom, a condition that ruined clam beds. In 1899 Iowa produced 20.3 pounds of shells but by 1908 this number had decreased to 4.6 million. (17) | ||

The Chalmers plant in Dubuque closed in 1930. (18) | |||

See: [[CULTURED PEARLS]] | |||

--- | |||

Source: | |||

1. Classen, Cheryl, "Washboards, Pigtoes, and Muckets: Historic Musseling in the Mississippi Watershed-Introduction," '''Historical Archaeology''', 1994, Online: file:///Users/randolphlyon/Downloads/BF03377143.pdf | |||

2. "The Pearl Button Story," '''Iowa Pathways''', Online: http://www.iptv.org/iowapathways/mypath.cfm?ounid=ob_000031 | |||

3. Kruse, Len. "Clamshell Buttons--Boom and Bust," '''My Old Dubuque''', Dubuque, Iowa: Center for Dubuque History, 2000. p. 252 | |||

4. "The Pearl Button Story." | |||

5. Kruse, Len., p. 252 | |||

6. Temte, Eric. "A Brief History of the Clamming and Pearling Industry in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. Wisconsin State University, 1968 Online: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=3&ved=0CE8QFjAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fminds.wisconsin.edu%2Fbitstream%2Fhandle%2F1793%2F47050%2Ftemteeric1968.pdf&ei=HdGkUumTLInTqgGrmICYAg&usg=AFQjCNEod_ASMrwDxDiBOJyUAbYqIwFiPA&sig2=-8oajsM2VId6YffFcvMBtA | |||

7. "Clamming," East Dubuque Local Area History Project, April 14, 2000, Online: http://www.eastdbqschools.org/archive/District/LocalAreaHistory/Clamminglah.htm | |||

8. Kruse, Len., p. 252 | |||

9. "Caught on the Fly," ''The Dubuque Herald'', March 18, 1898, p. 5 | |||

10. "A New Industry," '''Dubuque Herald''', May 1, 1898, p. 8 | |||

11. "Contracts Are Signed," ''Dubuque Daily Telegraph'', October 21, 1901, p. 3 | |||

12. Kruse | |||

13. "Contracts Are Signed..." | |||

14. Ibid., p. 253 | |||

15. "The Pearl Button Story." | |||

16. Kruse, Len. p. 253 | |||

17. Ibid. | |||

18. Ibid., p. 255 | |||

[[Category: Industry]] | [[Category: Industry]] | ||

Latest revision as of 18:06, 16 July 2025

BUTTON INDUSTRY. Mussels gathered from the rivers of the Mississippi watershed have supported two important industries and provided millions of dollars of income to land-based and river-based men and women starting in the 186Os.

Collecting freshwater pearls was the reason at first forharvesting shellfish from 1860 to 1900. The revenue for a single pearl was often in the thousands of dollars. "Pearl rushes" along a river created boomtown like environments which attracted local, as well as out-of-state, mussel-hunters and buyers. Proceeds from pearls brought to many individuals instant fortune and had an unheralded role in the capitalization of rural America prior to 1930. Pearl revenue exceeded all other natural product industries combined, excepting timber, in many areas.

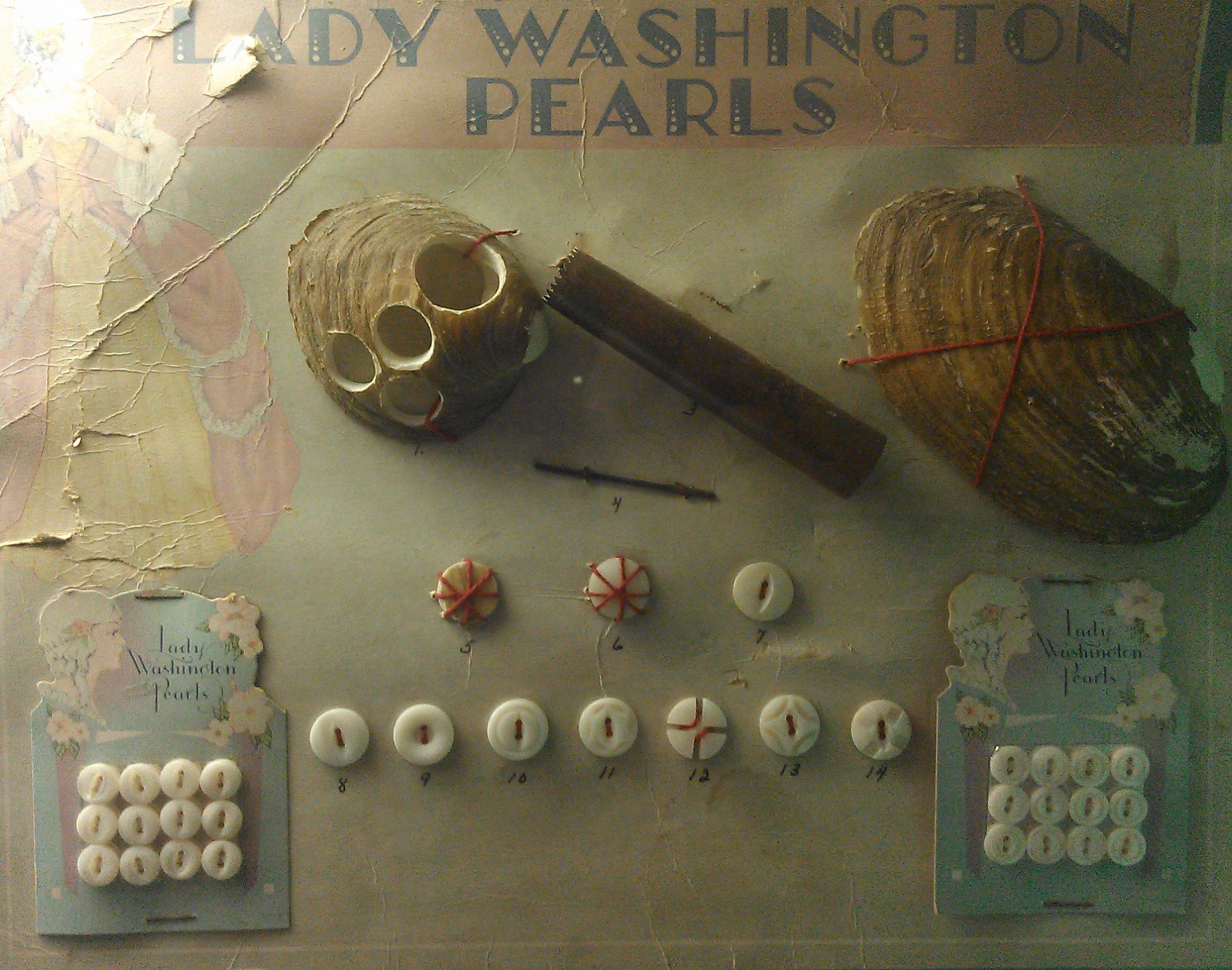

Most important of the commercial uses of river shellfish was the production of buttons from 1891 until approximately 1950. Shell buttons were made of both pearly ocean and freshwater shell for centuries in Europe before being manufactured in the northeastern United States beginning in the 1850s. The United States product, based on imported material, had a hard time competing with the European product, and the industry was dying out in 1890. (1)

The industry was brought to the midwestern United States by John BOEPPLE, a former German button maker, who was accustomed to using animal horn, hooves, bone and seashells. (2) In 1887 while looking for shells that were cheaper than those from the ocean for button production, he found several suitable beds of clams in rivers leading to the Mississippi. (3) In 1891 he established the Boepple Button Company, a pearl-button factory in Muscatine, Iowa. (4) In June 1900 near the mouth of CATFISH CREEK a small colony of clammers developed called "Pearl City." Living in tents, the clammers worked from June through October. (5)

Clamming was a low cost operation. Using a boat, a clammer would drag a rod with perhaps one hundred hooks along the river bottom. The clams would snap shut on the hook and be caught. The rod would be raised, the clams removed and the process repeated. Once the boat was full, it would be rowed to shore and unloaded. A clammer could earn three dollars for a full boat with the chance of finding a pearl which could bring one hundred dollars or more. (6)

The clams were placed in water and boiled. The meat was removed, checked for pearls, and then discarded or sold to farmers for hog feed or to fishermen for bait. It was also used for dog and cat food. (7) The shells were immediately sold to buyers or shipped to button factories. (8)

The industry caused an economic ripple effect into related industries such as housing and merchandising. Population increased in river cities as workers moved to new jobs that provided attractive year-round working conditions. The industry led to the development of a new group of wealthy Iowans who built mansions and invested their profits throughout their communities. The industry was not confined to cities along the Mississippi. In 1898 a large pearl button factory was opened in Vinton, Iowa by the Waterbury Button and Electric Company and local investors. Capitalized at $20,000, the company provided employment for between 70 and 100 people. Shells came from the Cedar River. (9)

Dubuque had the advantage of being close to the clam beds. In May, 1898 the Dubuque Herald reported "car loads of our mussel shells are being taken away." The article noted that the shells were destined for Muscatine, Iowa and a large pearl button factory. The article continued--

This new industry certainly opens a line of

employment which operates in an entirely new

field, and takes away many bushels of shells

which had always been considered worthless..

it is said in new territory men can make very

good wages at gathering them. (10)

The city also had a large source of labor and connections to cities of the eastern United States by RAILROADS. In March 1889, the Standard Pearl Button Company moved its machinery to Dubuque from Charles City. John Boepple visited Dubuque in 1898 and suggested his interest in moving his entire operation north from Muscatine if his moving expenses were reimbursed. This, however, was never done.

The largest button-making company to move to Dubuque was that of Harvey Chalmers and Son that established its own blank-cutting plant in the city in 1901. The company owned and operated the largest pearl button factory in the United States at Amsterdam, New York. At this plant, which employed an estimated 300 workers, only the finishing process in the manufacture of buttons was carried out. The rough work was carried out at branch locations like Dubuque. (11) Dubuque officials promised the company, named the Iroquois Pearl Button Company, the plant site for five years and installed the company's power plant for a total cost estimated to be $2,500. (12) The company promised to employ at least 150 men 300 days annually for a period of at least five years. If the company made good on its promises, it would receive a $500 bonus at the end of each year until the term of the agreement (five years) expired. The company posted a guarantee of $2,500 to ensure its good faith. (13) The company's location near the levee included three large buildings and two hundred button machines. (14)

With equipment sufficient to need a workforce of four hundred, the Iroquois Company encouraged employment by offering the unique opportunity for workers to earn money from the first day of employment, although at a reduced rate, while they were being trained. Similar factories paid no wages for the first two weeks. Women's jobs in button manufacturing were usually limited to the less skilled and lower paying positions. Cutters made an average of $8 to $10 a week. "Facers," drillers and packers—all positions filled by women—were paid between $4 and $6 a week. (15)

The slow pace of recruitment led the local press to remind workers that the job offered year-round employment. By 1902 the plant needed to be expanded at a cost of $30,000. (16) Cellars beneath the factory were said to store $45,000 worth of shells for winter processing.

Due to the size of its operation, the Iroquois plant was able to weather the financial collapse of the industry caused by speculation in 1903-1904.

Many factors led to the demise of the pearl button industry. Plastics developed near the time of World War II offered more variety in size, shape, and color than pearl buttons at much less cost. The ability of plastics to withstand detergents in washing has also been suggested. Construction of dams on the Mississippi and poor agricultural practices leading to erosion led to increased silting of the river bottom, a condition that ruined clam beds. In 1899 Iowa produced 20.3 pounds of shells but by 1908 this number had decreased to 4.6 million. (17)

The Chalmers plant in Dubuque closed in 1930. (18)

See: CULTURED PEARLS

---

Source:

1. Classen, Cheryl, "Washboards, Pigtoes, and Muckets: Historic Musseling in the Mississippi Watershed-Introduction," Historical Archaeology, 1994, Online: file:///Users/randolphlyon/Downloads/BF03377143.pdf

2. "The Pearl Button Story," Iowa Pathways, Online: http://www.iptv.org/iowapathways/mypath.cfm?ounid=ob_000031

3. Kruse, Len. "Clamshell Buttons--Boom and Bust," My Old Dubuque, Dubuque, Iowa: Center for Dubuque History, 2000. p. 252

4. "The Pearl Button Story."

5. Kruse, Len., p. 252

6. Temte, Eric. "A Brief History of the Clamming and Pearling Industry in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. Wisconsin State University, 1968 Online: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=3&ved=0CE8QFjAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fminds.wisconsin.edu%2Fbitstream%2Fhandle%2F1793%2F47050%2Ftemteeric1968.pdf&ei=HdGkUumTLInTqgGrmICYAg&usg=AFQjCNEod_ASMrwDxDiBOJyUAbYqIwFiPA&sig2=-8oajsM2VId6YffFcvMBtA

7. "Clamming," East Dubuque Local Area History Project, April 14, 2000, Online: http://www.eastdbqschools.org/archive/District/LocalAreaHistory/Clamminglah.htm

8. Kruse, Len., p. 252

9. "Caught on the Fly," The Dubuque Herald, March 18, 1898, p. 5

10. "A New Industry," Dubuque Herald, May 1, 1898, p. 8

11. "Contracts Are Signed," Dubuque Daily Telegraph, October 21, 1901, p. 3

12. Kruse

13. "Contracts Are Signed..."

14. Ibid., p. 253

15. "The Pearl Button Story."

16. Kruse, Len. p. 253

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid., p. 255