Encyclopedia Dubuque

"Encyclopedia Dubuque is the online authority for all things Dubuque, written by the people who know the city best.”

Marshall Cohen—researcher and producer, CNN

Affiliated with the Local History Network of the State Historical Society of Iowa, and the Iowa Museum Association.

CHICAGO GREAT WESTERN RAILROAD: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image:cgw.jpg|left|thumb|250px|c.1960]]CHICAGO GREAT WESTERN RAILROAD. In 1854, the Legislature of the Territory of Minnesota had chartered the Minnesota and Northwestern Railroad (M&NW) to be built between Lake Superior, Minneapolis and Dubuque, Iowa. Nothing was begun until the railroad was purchased by Alpheus Beede Stickney and other investors in 1883. Immediately, the railroad began building and acquiring other lines. (1) | |||

In September 1884, construction began and by October the road was operating between St. Paul, Minnesota southward to Lyle on the Minnesota-Iowa border. Late in 1885 the road reached Manly Junction in Worth County, Iowa which was on the Iowa Central railroad line. (2) | |||

In | [[Image:cgwP.png|left|thumb|250px|Railroad pass]]In the summer of 1885 the Minnesota and Northwestern announced that it wanted to acquire the Wisconsin, Iowa and Nebraska Railroad (WI&N) which was constructing track from Des Moines to Waterloo. At the time, the WI&N was attempting to acquire the Des Moines, Osceola and Southern which was completed from Des Moines to Cainsville, Missouri. (3) | ||

On June 1, 1886 Stickney and his associates reincorporated realizing the name Minnesota and Northwestern was misleading. Forming the Chicago, St. Paul and Kansas City Railway (CStP&KC), they purchased the WI&N which because of its route across Iowa was known as "The Old Diagonal" since its founding on March 17, 1882. (4) On November 30, 1886 the [[DUBUQUE AND NORTHWESTERN RAILROAD]] conveyed its property to the Minnesota and Northwestern Railroad Company of Minnesota. (5) This gave the Minnesota and Northwestern Railroad Company a complete line of railroad from St. Paul to Dubuque, the line from Hayfield to Lyle where it connected with the Illinois Central, and a line from Sumner west to Hampton, Iowa. (6) Early in 1887, the CStP&KC purchased the [[DUBUQUE AND DAKOTA RAILROAD]]. In 1887 the CStP&KC purchased all the property of the Minnesota and Northwestern. (7) | |||

By 1888 the Chicago, St. Paul and Kansas City Railroad (CStP&KC) had finished a continuous line all the way across Illinois to Forest Park, Illinois, except for trackage rights with the Illinois Central across the [[MISSISSIPPI RIVER]]. At Forest Park, Illinois the railroad made a connection with the Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal for the last nine miles into Chicago's Grand Central Station. The new construction included Illinois' longest railway bore, the Winston Tunnel, south of Galena. (8) To blow gas and smoke out of the tunnel, a 14-foot diameter fan operated by two diesel engines was installed. Since "Fanhouse" was located in a very isolated area, the fan operators on duty twenty-four hours daily, had to get to work by hand car. (9) | |||

Through merger and construction, the CStP&KC then added lines between Oelwein, Iowa, on the Chicago-to-St. Paul mainline, and Kansas City, Missouri, by 1891, and between Oelwein and Omaha, Nebraska by 1903. Oelwein became the hub of the railroad and its main locomotive repair shops were soon located there. The huge facility inspired Walter Chrysler, the future automobile manufacturer, who worked as the supervisor of the shops between 1904 and 1910 when he left after a dispute with Stickney's successor, Samuel Felton. (10) In his autobiography, '''Life of Ann American Workman,''' Chrysler wrote: | |||

They were the biggest shops I had ever seen. Sixteen or | |||

eighteen locomotives could be hauled inside them. In the | |||

winter darkness they were brilliantly illuminated with | |||

sputtering bluish arc lamps...when I saw the transfer | |||

tables I felt like applauding... (11) | |||

The Great Western also expanded its assortment of feeder branch lines in Iowa, Minnesota and Illinois, but plans to continue expanding the railroad north to Duluth, Minnesota, west to Sioux City, Iowa or Denver, Colorado, or south into Mexico, never occurred. | The Great Western also expanded its assortment of feeder branch lines in Iowa, Minnesota and Illinois, but plans to continue expanding the railroad north to Duluth, Minnesota, west to Sioux City, Iowa or Denver, Colorado, or south into Mexico, never occurred. | ||

The railroad survived the Panic of 1893 | A new rail line in the Midwest, the CStP&KC fought well-funded competitors. Aware of the rate cutting, rebating and other forms of discrimination used by railroads at the time, he strongly supported one rate for all shippers for a specific commodity between two given points. (12) In a meeting with other railroad presidents, it is said he complimented each as a person of honesty and fine character before adding, "...but as railroad presidents I would not trust any one of you with my watch." (13) By 1892, however, his railroad was near financial ruin. He avoided receivership by reorganizing the road as the Chicago Great Western Railway. | ||

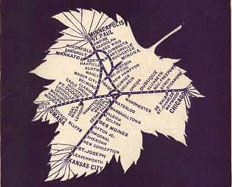

[[Image:mapleleaf1.jpg|left|thumb|250px|Maple Leaf]]The railroad survived the Panic of 1893 because the new company had no mortgage indebtedness. (14) With Stickney leading, the company developed a reputation for being an innovative and progressive competitor. The locomotives' stacks were painted a bright red giving the Great Western the nickname "The Red Stack." (15) It was around this time that R. G. Thompson, an employee at For Wayne, Indiana, won the award for designing the best emblem for the company. Thompson designed a maple leaf on which the veins showed the lines of the railway. Throughout Stickney's remaining years with the railroad, the emblem was used on all timetables and advertising. | |||

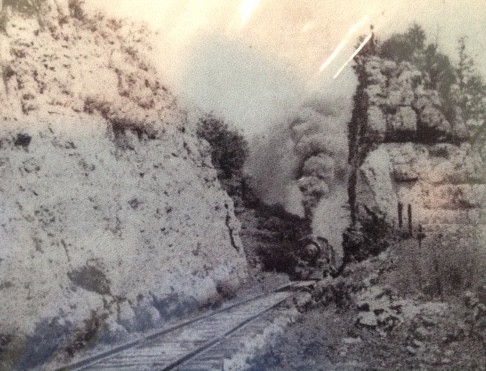

[[Image:IMG_5380.JPG|left|thumb|250px|A steam locomotive belonging to the Chicago Great Western (c.1900) squeezes through the rock cut west of Durango and north of Dubuque. This later became part of [[HERITAGE TRAIL]]. Photo courtesy: Bob Reding]]The Panic of 1907 forced the railroad into bankruptcy, and the road was purchased by financial interests associated with J. P. Morgan. In 1909 the road was sold with its properties transferred to the Chicago Great Western Railroad. (16) Stickney was forced out and replaced by Samuel Morse Felton, Jr. in 1909. | |||

Felton | [[Image:cornbelt.jpg|left|thumb|250px|Corn Belt logo]]Felton realized that the railroad could not survive in the fiercely competitive markets it served without an ambitious and sustained effort to innovate and modernize. The main passenger train was the Great Western Limited operating between Chicago and Minneapolis. Advertisements from the time stated: | ||

Passengers will find all the comforts of home and the | |||

club on this new train, which leaves Chicago at 6:30 p.m. | |||

daily. There is a car for every travel need--sleepers with | |||

large berths, drawing-rooms and compartments, dining-car | |||

service, a Club car, as comfortable as the library of a | |||

metropolitan club, with club conveniences, and new clean | |||

comfortable chair cars and coaches, all brilliantly electric | |||

lighted. (17) | |||

Gasoline-powered motorcars replaced steam power on the passenger trains. The "maple leaf" logo was replaced with a "Corn Belt Route" emblem. (18) | |||

[[Image:IMG_5382.JPG|left|thumb|350px|Most of the operation conducted by the Chicago Great Western Railroad were carried out at the Fairgrounds Yards located west of Peru Road. The yard office was nearly under the former 32nd Street Overpass. Photo courtesy: Bob Reding]]Felton admired the trim, clean look of British locomotives. Returning to the United States he had a conventional Pacific-type locomotive rebuilt so that all outside pipes were concealed. The driving rods and cylinder heads were polished, the wheels painted red, and the spokes were golden. Engine No. 916 with its four cars were painted Venetian red with gold lettering. Dubbed the "Red Bird," the train ran nonstop between the Twin Cities and Rochester, Minnesota. Six years later, the designers came up with a motor-train painted blue with striping and lettering in gold leaf. Named the "Blue Bird" the train featured a passenger car seating seventy-four and a parlor-observation car. The car also had two complete Pullman sections with seats that could be converted to berths--appreciated by patients headed for the Mayo Clinic. (19) | |||

[[Image:IMG_5385.JPG|left|thumb|350px|The Chicago Great Western Railroad depot was located at the foot of East 8th Street at Elm. This building served the needs of Dubuque for over 70 years.Photo courtesy: Bob Reding]]Felton retired in 1929. At the time he stepped down, investors friendly with Patrick H. Joyce had purchased a controlling interest in the Great Western from J. P. Morgan and had placed him in charge of the railroad. In 1935, the railroad declared bankruptcy again. It was reorganized and re-emerged in 1941 as the Chicago Great Western Railway. (20) | |||

Despite the financial mismanagement, Joyce continued the modernization and innovation of his predecessors. The Great Western trimmed passenger service, which was never particularly profitable on the lightly-populated lines, abandoned branch lines and refurbished main lines, and continued acquisition of huge locomotives which pulled enormous trains, sometimes one-hundred cars long and longer. The most important innovation was the so-called "Piggyback Service", the predecessor of modern intermodal freight transport. Introduced in 1936 truck trailers were carried on specially modified flat cars between Chicago and St. Paul. (21) The Great Western was also an early proponent of diesel power. It purchased its first diesel-electric locomotive, an 800-horsepower yard switcher from Westinghouse, in 1934, and was completely converted to diesel power by 1950. (22) | |||

As this was happening, a group of businessmen friendly to William N. Deramus, Jr., president of the Kansas City Southern, purchased a controlling share of Great Western stock, and by 1949, this group appointed Deramus' son, William N. Deramus III, to head the railroad. He continued the modernization and cost-trimming. Passenger service was almost entirely eliminated, unprofitable dining and sleeping car service was discontinued and the railroad's offices, spread out in Chicago and throughout the system, were consolidated in Oelwein. Even longer trains than before, pulled by sets of five or more EMD F-units, became standard operating procedure, which hurt service but increased efficiency. (23) | |||

In 1946, the first proposal to merge the Great Western with other railroads, this time with the Chicago and Eastern Illinois Railroad and the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad. Investors hesitated, and the CGW stayed independent. (24) | |||

Upon his resignation, Deramus was replaced by Edward T. Reidy. As before, innovations continued to keep the company profitable. Second-generation diesel locomotives such as the EMD GP30 and EMD SD40, the largest and most powerful the CGW ever owned, were used and the Oelwein shops stayed busy repairing and maintaining the now-aged F-units long after many other railroads had replaced theirs. Passenger service, reduced to two St. Paul to Omaha trains, was gone by 1962. Labor costs were trimmed, branch lines abandoned, as the Great Western tried to stay a potential merger partner. (25) | |||

The CGW was open to a merger bid with the Chicago and North Western Railway (CNW), first proposed in 1964. On July 1, 1968, the Chicago Great Western merged with Chicago and North Western. The CNW maintained the facilities at Oelwein for several years, but ultimately abandoned the yard and shops. Within a decade, most of the CGW right-of-way had been abandoned by the CNW. (26) | |||

[[Image:CGW.png|left|thumb|150px|]] The railroad had stopped service to Dyersville in 1956, and the depot was demolished in 1972. In the 1980s the decision was made by the railroad's parent corporation to abandon the line. A scramble started among conservation people, adjoining landowners and bicyclists who sought to create a bike path on the former right-of-way. (27) Eventually the bicyclists won and [[HERITAGE TRAIL]] was created. | |||

--- | --- | ||

| Line 53: | Line 66: | ||

4. Donovan | 4. Donovan | ||

5. | 5. "A Brief History Of the Construction And Operation of the Chicago Great Western Railway Company," Train Web. Online: http://trainweb.org/ucgw/hsfcgw10.htm | ||

6. Ibid. | |||

7. Donovan | |||

8. Finch, p. 253 | |||

9. Ibid., p. 254 | |||

10. Donovan, p. 59 | |||

11. Ibid. | |||

12. Ibid. | |||

13. Ibid., p. 59 | |||

14. Ibid., p. 55 | |||

15. Ibid., p. 59 | |||

16. Ibid. p. 60 | |||

17. Finch, p. 298 | |||

18. Donovan, p. 61 | |||

19. Ibid. p. 62 | |||

20. "History of the Chicago Great Western," | |||

21. Ibid. | |||

22. Ibid. | |||

23. Ibid. | |||

24. Ibid. | |||

25. Ibid. | |||

26. Ibid. | |||

27. Finch, p. 260 | |||

[[Category: Railroad]] | [[Category: Railroad]] | ||

[[Category: Railroad passes} | |||

Latest revision as of 17:29, 7 January 2019

CHICAGO GREAT WESTERN RAILROAD. In 1854, the Legislature of the Territory of Minnesota had chartered the Minnesota and Northwestern Railroad (M&NW) to be built between Lake Superior, Minneapolis and Dubuque, Iowa. Nothing was begun until the railroad was purchased by Alpheus Beede Stickney and other investors in 1883. Immediately, the railroad began building and acquiring other lines. (1)

In September 1884, construction began and by October the road was operating between St. Paul, Minnesota southward to Lyle on the Minnesota-Iowa border. Late in 1885 the road reached Manly Junction in Worth County, Iowa which was on the Iowa Central railroad line. (2)

In the summer of 1885 the Minnesota and Northwestern announced that it wanted to acquire the Wisconsin, Iowa and Nebraska Railroad (WI&N) which was constructing track from Des Moines to Waterloo. At the time, the WI&N was attempting to acquire the Des Moines, Osceola and Southern which was completed from Des Moines to Cainsville, Missouri. (3)

On June 1, 1886 Stickney and his associates reincorporated realizing the name Minnesota and Northwestern was misleading. Forming the Chicago, St. Paul and Kansas City Railway (CStP&KC), they purchased the WI&N which because of its route across Iowa was known as "The Old Diagonal" since its founding on March 17, 1882. (4) On November 30, 1886 the DUBUQUE AND NORTHWESTERN RAILROAD conveyed its property to the Minnesota and Northwestern Railroad Company of Minnesota. (5) This gave the Minnesota and Northwestern Railroad Company a complete line of railroad from St. Paul to Dubuque, the line from Hayfield to Lyle where it connected with the Illinois Central, and a line from Sumner west to Hampton, Iowa. (6) Early in 1887, the CStP&KC purchased the DUBUQUE AND DAKOTA RAILROAD. In 1887 the CStP&KC purchased all the property of the Minnesota and Northwestern. (7)

By 1888 the Chicago, St. Paul and Kansas City Railroad (CStP&KC) had finished a continuous line all the way across Illinois to Forest Park, Illinois, except for trackage rights with the Illinois Central across the MISSISSIPPI RIVER. At Forest Park, Illinois the railroad made a connection with the Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal for the last nine miles into Chicago's Grand Central Station. The new construction included Illinois' longest railway bore, the Winston Tunnel, south of Galena. (8) To blow gas and smoke out of the tunnel, a 14-foot diameter fan operated by two diesel engines was installed. Since "Fanhouse" was located in a very isolated area, the fan operators on duty twenty-four hours daily, had to get to work by hand car. (9)

Through merger and construction, the CStP&KC then added lines between Oelwein, Iowa, on the Chicago-to-St. Paul mainline, and Kansas City, Missouri, by 1891, and between Oelwein and Omaha, Nebraska by 1903. Oelwein became the hub of the railroad and its main locomotive repair shops were soon located there. The huge facility inspired Walter Chrysler, the future automobile manufacturer, who worked as the supervisor of the shops between 1904 and 1910 when he left after a dispute with Stickney's successor, Samuel Felton. (10) In his autobiography, Life of Ann American Workman, Chrysler wrote:

They were the biggest shops I had ever seen. Sixteen or

eighteen locomotives could be hauled inside them. In the

winter darkness they were brilliantly illuminated with

sputtering bluish arc lamps...when I saw the transfer

tables I felt like applauding... (11)

The Great Western also expanded its assortment of feeder branch lines in Iowa, Minnesota and Illinois, but plans to continue expanding the railroad north to Duluth, Minnesota, west to Sioux City, Iowa or Denver, Colorado, or south into Mexico, never occurred.

A new rail line in the Midwest, the CStP&KC fought well-funded competitors. Aware of the rate cutting, rebating and other forms of discrimination used by railroads at the time, he strongly supported one rate for all shippers for a specific commodity between two given points. (12) In a meeting with other railroad presidents, it is said he complimented each as a person of honesty and fine character before adding, "...but as railroad presidents I would not trust any one of you with my watch." (13) By 1892, however, his railroad was near financial ruin. He avoided receivership by reorganizing the road as the Chicago Great Western Railway.

The railroad survived the Panic of 1893 because the new company had no mortgage indebtedness. (14) With Stickney leading, the company developed a reputation for being an innovative and progressive competitor. The locomotives' stacks were painted a bright red giving the Great Western the nickname "The Red Stack." (15) It was around this time that R. G. Thompson, an employee at For Wayne, Indiana, won the award for designing the best emblem for the company. Thompson designed a maple leaf on which the veins showed the lines of the railway. Throughout Stickney's remaining years with the railroad, the emblem was used on all timetables and advertising.

The Panic of 1907 forced the railroad into bankruptcy, and the road was purchased by financial interests associated with J. P. Morgan. In 1909 the road was sold with its properties transferred to the Chicago Great Western Railroad. (16) Stickney was forced out and replaced by Samuel Morse Felton, Jr. in 1909.

Felton realized that the railroad could not survive in the fiercely competitive markets it served without an ambitious and sustained effort to innovate and modernize. The main passenger train was the Great Western Limited operating between Chicago and Minneapolis. Advertisements from the time stated:

Passengers will find all the comforts of home and the

club on this new train, which leaves Chicago at 6:30 p.m.

daily. There is a car for every travel need--sleepers with

large berths, drawing-rooms and compartments, dining-car

service, a Club car, as comfortable as the library of a

metropolitan club, with club conveniences, and new clean

comfortable chair cars and coaches, all brilliantly electric

lighted. (17)

Gasoline-powered motorcars replaced steam power on the passenger trains. The "maple leaf" logo was replaced with a "Corn Belt Route" emblem. (18)

Felton admired the trim, clean look of British locomotives. Returning to the United States he had a conventional Pacific-type locomotive rebuilt so that all outside pipes were concealed. The driving rods and cylinder heads were polished, the wheels painted red, and the spokes were golden. Engine No. 916 with its four cars were painted Venetian red with gold lettering. Dubbed the "Red Bird," the train ran nonstop between the Twin Cities and Rochester, Minnesota. Six years later, the designers came up with a motor-train painted blue with striping and lettering in gold leaf. Named the "Blue Bird" the train featured a passenger car seating seventy-four and a parlor-observation car. The car also had two complete Pullman sections with seats that could be converted to berths--appreciated by patients headed for the Mayo Clinic. (19)

Felton retired in 1929. At the time he stepped down, investors friendly with Patrick H. Joyce had purchased a controlling interest in the Great Western from J. P. Morgan and had placed him in charge of the railroad. In 1935, the railroad declared bankruptcy again. It was reorganized and re-emerged in 1941 as the Chicago Great Western Railway. (20)

Despite the financial mismanagement, Joyce continued the modernization and innovation of his predecessors. The Great Western trimmed passenger service, which was never particularly profitable on the lightly-populated lines, abandoned branch lines and refurbished main lines, and continued acquisition of huge locomotives which pulled enormous trains, sometimes one-hundred cars long and longer. The most important innovation was the so-called "Piggyback Service", the predecessor of modern intermodal freight transport. Introduced in 1936 truck trailers were carried on specially modified flat cars between Chicago and St. Paul. (21) The Great Western was also an early proponent of diesel power. It purchased its first diesel-electric locomotive, an 800-horsepower yard switcher from Westinghouse, in 1934, and was completely converted to diesel power by 1950. (22)

As this was happening, a group of businessmen friendly to William N. Deramus, Jr., president of the Kansas City Southern, purchased a controlling share of Great Western stock, and by 1949, this group appointed Deramus' son, William N. Deramus III, to head the railroad. He continued the modernization and cost-trimming. Passenger service was almost entirely eliminated, unprofitable dining and sleeping car service was discontinued and the railroad's offices, spread out in Chicago and throughout the system, were consolidated in Oelwein. Even longer trains than before, pulled by sets of five or more EMD F-units, became standard operating procedure, which hurt service but increased efficiency. (23)

In 1946, the first proposal to merge the Great Western with other railroads, this time with the Chicago and Eastern Illinois Railroad and the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad. Investors hesitated, and the CGW stayed independent. (24)

Upon his resignation, Deramus was replaced by Edward T. Reidy. As before, innovations continued to keep the company profitable. Second-generation diesel locomotives such as the EMD GP30 and EMD SD40, the largest and most powerful the CGW ever owned, were used and the Oelwein shops stayed busy repairing and maintaining the now-aged F-units long after many other railroads had replaced theirs. Passenger service, reduced to two St. Paul to Omaha trains, was gone by 1962. Labor costs were trimmed, branch lines abandoned, as the Great Western tried to stay a potential merger partner. (25)

The CGW was open to a merger bid with the Chicago and North Western Railway (CNW), first proposed in 1964. On July 1, 1968, the Chicago Great Western merged with Chicago and North Western. The CNW maintained the facilities at Oelwein for several years, but ultimately abandoned the yard and shops. Within a decade, most of the CGW right-of-way had been abandoned by the CNW. (26)

The railroad had stopped service to Dyersville in 1956, and the depot was demolished in 1972. In the 1980s the decision was made by the railroad's parent corporation to abandon the line. A scramble started among conservation people, adjoining landowners and bicyclists who sought to create a bike path on the former right-of-way. (27) Eventually the bicyclists won and HERITAGE TRAIL was created.

---

Source:

1. "History of the Chicago Great Western," Online: http://www.cgwoelwein.com/cgwhistory.html

2. Donovan, Frank P. Iowa Railroads, Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2000, p. 53

3. Finch, Charles W. Our American Railroads; The Way It Was, East Dubuque, IL, Register Printing Company, 1988, p. 118

4. Donovan

5. "A Brief History Of the Construction And Operation of the Chicago Great Western Railway Company," Train Web. Online: http://trainweb.org/ucgw/hsfcgw10.htm

6. Ibid.

7. Donovan

8. Finch, p. 253

9. Ibid., p. 254

10. Donovan, p. 59

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid., p. 59

14. Ibid., p. 55

15. Ibid., p. 59

16. Ibid. p. 60

17. Finch, p. 298

18. Donovan, p. 61

19. Ibid. p. 62

20. "History of the Chicago Great Western,"

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. Finch, p. 260 [[Category: Railroad passes}